Die Kurzantwort auf die Einstiegsfrage lautet "Ja, mit einer differenzierten Stellungnahme", so Medienexperte Karmasin. Die Geschäftsideologie der Sozialen Medien fördere Polarisierung, davon würden extreme Ränder profitieren und das Vertrauen in Politik, Wissenschaft und Medien würde so schwinden. Es herrsche wenig Regulierung, womit liberale Demokratien in den Sozialen Netzwerken im "luftleerem Raum" stehen würden. Laut dem Forschungsergebnis hätten Facebook, Instagram, Twitter und Co. positive Effekte in Autokratien, aber würden sich auf liberale Demokratien "verstärkt negativ" auswirken. Die Wissenschaftler:innen kamen folglich zum pessimistischen Schluss, dass soziale Netzwerke nicht wie erwartet Meinungsvielfalt und die Teilhabe an Diskursen fördern, sondern paradoxerweise das Gegenteil bewirken.

Die Wissenschaftler:innen warnen in der Studie allerdings nicht nur vor Polarisierung und Meinungsmanipulation, sondern sprechen Empfehlungen aus, die sie an die politischen Entscheidungsträger:innen richten. So halten sie zum Beispiel die Einsetzung eines Ethikrats für politische Werbung und PR in Sozialen Medien für sinnvoll, empfehlen eine Reform der Medienförderung oder sehen eine Stärkung demokratischer Kontrolle über digitale Plattformen vor.

Die gesamte Stellungnahme der Ad-Hoc-Arbeitsgruppe der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften finden Sie hier.

Eine Einordung und Zusammenfassung der gesamten Veranstaltung im Österreichischen Parlament ist hier nachzulesen.

Im März 2023 wurde der "Rat für die zukünftige Entwicklung des öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunks" (Zukunftsrat) eingesetzt, damit eine "langfristige Perspektive für die Öffentlich-Rechtlichen" entwickelt werden kann. Dem Zukunftsrat wurde anvertraut; "einen Bericht mit Empfehlungen für die Zukunft des öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunks, seiner künftigen Nutzung und dessen Akzeptanz" zu erarbeiten. Argumentiert wird im Bericht damit, dass es mit einer "vorwiegend bewahrenden Weiterführung" nicht getan sein kann und es einer umfassenden Reform des Öffentlich-Rechtlichen bedarf.

Inzwischen hat sich gerade junges Publikum abgewandt. Der Zukunftsrat legt in seinem Bericht zehn Vorschläge für Reformen dar, die möglichst rasch umgesetzt werden sollten, um die Akzeptanz des Öffentlich-Rechtlichen Rundfunks zu steigern.

Die Empfehlungen des Zukunftsrats zusammengefasst:

1.

Der Angebotsauftrag der Öffentlich-Rechtlichen soll in zentralen Aspekten geschärft und weiterentwickelt werden. Dabei wäre ein stärkerer Fokus auf die Demokratie- und Gemeinwohlorientierung wünschenswert, "mit dem Ziel, die Öffentlich-Rechtlichen stärker auf ihren Beitrag zur demokratischen Selbstverständigung zu verpflichten."

2.

Öffentlich-rechtliche Anstalten sollen Menschen zusammenbringen. Auch das sollte im Angebotsauftrag verankert sein.

3.

Öffentlich-rechtliche Anstalten sollten für alle da sein, die dauerhaft in Deutschland leben und als zukünftige Wähler:innen infrage kommen.

4.

Digitale Teilhabe sollte ein zentraler Aspekt des Angebotsauftrags sein. Gerade non-lineare Format würden sich besonders zur "Selbstverständigung der Gesellschaft" eignen.

5.

Der öffentlich-rechtliche Auftrag lässt sich hinsichtlich der Werte "Eigenständigkeit und Unterscheidbarkeit", "Unabhängigkeit" und "Ausgewogenheit" stärken.

6.

Der Zukunftsrat empfiehlt für ARD, ZDF und Deutschlandradio "jeweils einen pluralistisch besetzten Medienrat als Hüter der Auftragserfüllung, einen überwiegend nach Fachexpertise besetzten Verwaltungsrat zur Stärkung von Strategiefähigkeit und Kontrolle und eine kollegiale Geschäftsleitung vor." Bisherige Organe sollen ersetzt werden.

7.

Es wird eine ARD-Anstalt mit "zentraler Leitung" empfohlen, die die Arbeitsgemeinschaft ersetzt. Sie soll als Dachorganisation der Landesrundfunkanstalten dienen. "Das Modell folgt dem Gedanken der organisierten Regionalität: Zentrales zentral, Regionales regional."

8.

Der Zukunftsrat empfiehlt eine "Gesellschaft für die Entwicklung und den Betrieb einer gemeinsamen technologischen Plattform zu gründen." Diese Gesellschaft hat zum Zweck, das technische System für alle öffentlich-rechtlichen digitalen Plattformen bereitzustellen. In ihr sollen keine Inhalte entstehen, die drei Partner sollen inhaltlich autonom bleiben.

9.

Der Zukunftsrat ist der Ansicht, es sei notwendig, die Bereitschaft zur Veränderung auch innerhalb der öffentlich-rechtlichen Anstalten zu fördern: "Ein gutes Angebot braucht gute Köpfe." Dies inkludiert die Steigerung der Managementkompetenz, "um Fortbildungen zu verbessern und Externe zu gewinnen." Außerdem beinhaltet dies "funktionsadäquate Gehälter."

10.

Die abschließende Empfehlung des Zukunftsrates ist die "Umstellung des Finanzierungsverfahrens der Öffentlich-Rechtlichen." Hierzu heißt es im Dokument: "Dabei soll die Ex-ante-Bewertung durch die Kommission zur Überprüfung und Ermittlung des Finanzbedarfs der Rundfunkanstalten (KEF) durch eine am Maßstab der Auftragserfüllung ausgerichtete Ex-post-Bewertung von einer modifizierten KEF ersetzt werden. Entsprechende Bewertungskriterien sind staatsvertraglich festzulegen. Was die Höhe des Beitrags betrifft, geht der Zukunftsrat von einem Modell aus, das Auftragserfüllung und Indexierung kombiniert, wobei die vorgeschlagenen Reformen mittelfristig zu signifikanten Einsparungen führen werden. Inwieweit diese zur Absenkung des Rundfunkbeitrags oder zur besseren Auftragserfüllung verwendet werden, müssen die Länder entscheiden."

Der gesamte Bericht ist hier zu finden.

Die DialogForen werden auf zukunft.ORF.at live gestreamt und zeitversetzt auf ORF III ausgestrahlt.

Das neue Jahr beginnt mit einem neuen ORF Programm. Dem eben in Kraft getretenen ORF-Gesetz folgend bietet der ORF ab 2024 ein exklusives Angebot für die jüngste Generation. Wie wird es aussehen? Was plant der ORF? Welche Erwartungen haben Expertinnen und Experten, vor allem aber die Kinder selbst?

Im DialogForum diskutieren:

Jessica Braunegger, Kinderbüro

Maya Götz, Internationales Zentralinstitut für das Jugend- und Bildungsfernsehen

Yvonne Lacina-Blaha, ORF KIDS

Judith Ranftler, Volkshilfe

Jeanette Steemers, King's College London

Martina Thiele, Universität Tübingen

Die DialogForen werden auf zukunft.ORF.at live gestreamt und zeitversetzt auf ORF III ausgestrahlt.

Ob Fernsehfilm oder Musikshow, ob Kabarett oder Comedy - Die Unterhaltung ist die größte Programmsäule im Fernsehen. Steckt mehr darin als Lust und Laune, gibt es Haltung und Bildung samt Herz und Schmerz? Welche Qualitätskriterien sollen gelten? Welche Verpflichtungen, welche No-Gos machen öffentlich-rechtliche Unterhaltung aus?

Aus Anlass der neuen Public Value Studie "Die Bedeutung öffentlich-rechtlicher Unterhaltung in Zeiten des digitalen Wandels" diskutieren im DialogForum. Aus Anlass der neuen Public Value Studie "Die Bedeutung öffentlich-rechtlicher Unterhaltung in Zeiten des digitalen Wandels" diskutieren im DialogForum

Anne Bartsch, Universität Leipzig

Stefan Zechner, ORF TV-Unterhaltung

Rafael Haigermoser, Bundesjugendvertretung

Florence Hartmann, European Broadcasting Union

Matthias Kettemann, Universität Innsbruck

Ronja Kok, Österreichische Pfadfinderin

Leonie-Rachel Soyel, Influencerin

Gerald Szyszkowitz, Autor "Wie man wird, was man sein möchte"

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger, ORF Public Value

Die DialogForen werden zeitversetzt auf ORF III Kultur und Information ausgestrahlt.

Wie sieht die Vision eines besseren öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunks aus?

Der ÖRR steckt nicht nur in Österreich inmitten einer Legitimationskrise und wird von vielen Seiten kritisiert. Wie ein moderner öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk aussehen könnte, wird in dem Format DIE DA OBEN! des ARD/ZDF-Content-Netzwerks funk mithilfe eines Gedankenexperiments thematisiert. Einen ÖRR neu zu erfinden, sodass er den heutigen Anforderungen gerecht wird, versuchen verschiedene Medienexpert:innen und Wissenschaftler:innen gemeinsam mit ehemaligen Mitarbeitenden öffentlich-rechtlicher Anstalten. Im Rahmen der Recherche wurde auch die Community von DIE DA OBEN! befragt, was ihrer Meinung nach einen richtig guten öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunk ausmachen würde.

Fünf Anforderungen der befragen Expert:innen an den öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunk

1. Verlässliche Informationen

Ein neuer ÖRR sollte weiterhin verlässliche und qualitativ hochwertige Informationen bereitstellen. Durch eine fundierte Recherche und eine transparente Berichterstattung könne er das Vertrauen der Zuschauer:innen gewinnen und aufrechterhalten. Im Zeitalter von Fake News und Vertrauenskrise ist das Angebot von geprüften Informationen unabdingbar.

2. Unabhängigkeit

Um glaubwürdig zu sein, muss ein ÖRR unabhängig von wirtschaftlichen Interessen und politischem Druck agieren. Eine klare Trennung von Journalismus und kommerziellen Interessen ist notwendig, um eine objektive Berichterstattung sicherzustellen.

3. Content für alle

Der ideale ÖRR sollte Inhalte produzieren, die für die gesamte Gesellschaft relevant sind. Das bedeutet, dass er die Interessen und Bedürfnisse verschiedener Zielgruppen berücksichtigen und ein vielfältiges Programm anbieten sollte.

4. Meinungsaustausch befördern

Ein ÖRR sollte als Plattform für Meinungsaustausch dienen und zahlreiche Standpunkte berücksichtigen. Gesellschaftlich relevante Themen sollten in Diskussionen beleuchtet und ein breites Meinungsspektrum abgebildet werden.

5. Zusammenhalt und Demokratie stärken

Indem der neue ÖRR die Vielfalt der Gesellschaft widerspiegelt und unterschiedliche Perspektiven einbezieht, könnte er das Verständnis füreinander fördern und zur demokratischen Meinungsbildung beitragen.

Ein neuer öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk könnte weiters nur bestehen, wenn er dem Motto "digital first" folgt. Die Expert:innen betonen, dass ein moderner ÖRR den digitalen Wandel aktiv nutzen und seine Inhalte auf verschiedenen Plattformen wie Online-Portalen, sozialen Medien und Streaming-Diensten zugänglich machen sollte.

Vor allem die befragte Community wünscht sich vielfältigeren Content und bemängelt sich häufig wiederholende Inhalte. Eine effiziente Planung und Koordination der Inhalte würde sicherstellen, dass kein doppelter Content produziert wird. Dadurch könnten Kapazitäten frei werden, die für andere wichtige Themen genutzt werden könnten.

Nun zu der spannenden Frage: Welchen Content macht ein solcher moderner ÖRR & was ist noch zu beachten?

Regionalität & Internationalität

Gewünscht werden vor allem regionale und lokale Inhalte - mit einem ausgebauten Korrespondent:innen-Netzwerk könnten auch internationale Themen abgedeckt werden.

Unterhaltung mit Mehrwert

Im Bereich der Unterhaltung wird der Wunsch nach Unterhaltung, die zum Nachdenken anregt, laut.

Inhalte für junge Menschen

Insgesamt sollte ein moderner ÖRR verstärkt Inhalte produzieren, die junge Menschen ansprechen und ihre Interessen und Bedürfnisse berücksichtigen.

Faktencheck

Der neue Öffentlich-Rechtliche erhält die Aufgabe (problematischen) Content anderer Quellen einzuordnen und mithilfe von Recherche und Faktencheck gegebenenfalls zu falsifizieren. Fundierte und ausgewogene Inhalte sind hier die Devise.

Innovation: Mut zu Trial & Error

Betont wird auch immer wieder, dass ein moderner ÖRR Mut zu Trial & Error aufbringen muss - mehr Innovation und neue Technik sind klare Forderungen an diesen.

Creative Commons Lizenz

Teilweise plädieren Wissenschaftler:innen für eine Creative Commons Lizenz, denn damit wird die Nutzung und Verbreitung von öffentlich-rechtlichen Inhalte erleichtert.

Einbinden der Community auf verschiedenen Ebenen

Die befragten Expert:innen schlagen eine Publikumsversammlung, die über die Leitlinien entscheidet, vor, um den demokratischen Faktor zu verstärken. Eine weitere Möglichkeit ist ein Community-Rat (ein demokratischer Publikumsrat), der aus freiwilligen Nutzer:innen besteht. Ombudsstellen sollten eingerichtet werden, um Feedback von den Zuseher:innen entgegenzunehmen und auf deren Anliegen einzugehen. Kommentare sind ein wichtiges Instrument dieser Rückmeldungen, aber auch notwendig für einen direkten Austausch. Deswegen sollte bei jedem öffentlich-rechtlichen Angebot eine Kommentarfunktion gegeben sein.

Wie wird der ÖRR in diesem Gedankenexperiment organisiert?

Notwendig ist eine Reduktion der Bürokratie, denn verkrustete Strukturen haben Einfluss auf den Output und beschränken die Möglichkeiten des ÖRR. Die einzelnen Studios sollen nicht mehr alle Bereiche abdecken, sondern Schwerpunkte und bei großen Themen auf Zusammenarbeit setzen.

Digitale Technologien ermöglichen flexible Workflows und eine zentrale Verwaltung. Dadurch könnten Prozesse optimiert und die Zusammenarbeit erleichtert werden.

Eine angemessene und faire Bezahlung aller Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter sollte gewährleistet sein. Flachere Gehaltshierarchien könnten zu einer gerechteren Verteilung der finanziellen Mittel beitragen.

Insgesamt, so das Fazit des Gedankenexperiments, wäre ein neuer öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk, der sich an den genannten Prinzipien orientiert, in der Lage, den heutigen Herausforderungen und Bedürfnissen gerecht zu werden.

Ein solcher ÖRR würde eine vielfältige und qualitativ hochwertige Medienlandschaft unterstützen, die zur Förderung der Gesellschaft und Demokratie beiträgt.

Das ungekürzte Gedankenexperiment von funk findet finden Sie hier.

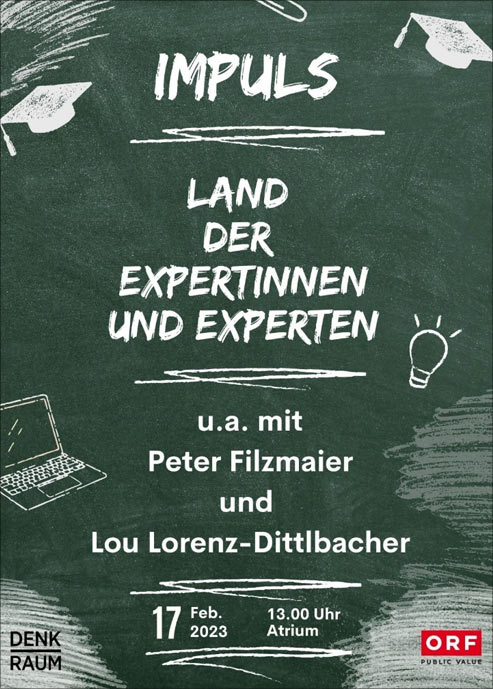

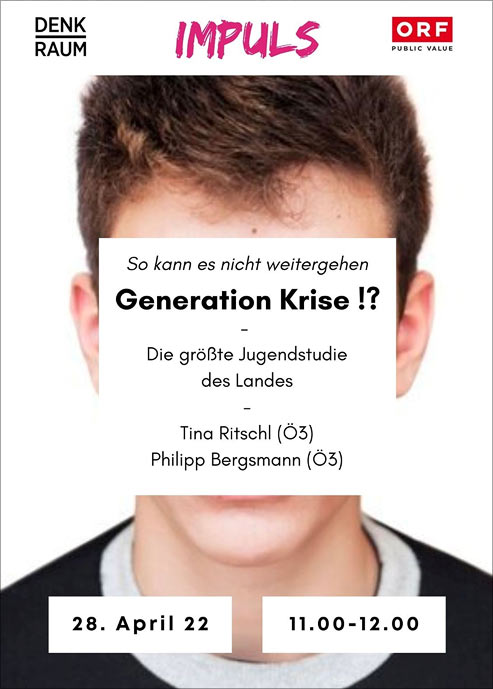

Die Vermittlung von unabhängiger und qualifizierter Fachmeinung ist ein maßgebliches Qualitätsmerkmal für die journalistische Arbeit - sie schafft Vertrauen, Orientierung und Ausgewogenheit. Wie mit dieser hochsensiblen Angelegenheit umgegangen und wer letzten Endes interviewt wird, ist Teil von stetiger, kritischer Selbstreflexion in den Redaktionen und den einzelnen Gestalter:innen. Dies betrifft auch die geschlechtsspezifisch ausgewogene Repräsentation von Expertinnen und Experten.

Doch Expertinnen sind in den ORF-Medien nach wie vor unterrepräsentiert. "Der Experte" ist sehr oft immer noch "alt, weiß und männlich" konnotiert. Eine pluralistische Gesellschaft verlangt jedoch mehr Diversität.

Vor diesem Hintergrund gibt es im ORF seit 2021 eine Expertinnen-Datenbank. Sie dient den Redaktionen als Austausch- und Rechercheplattform von Expertinnen aus unterschiedlichen Fachbereichen und geografischen Regionen Österreichs. Alle Redakteur:innen haben die Möglichkeit selbst Expertinnen in die Datenbank einzutragen und damit dem gesamten Kollegium im ORF weiterzuempfehlen sowie selbst nach Expertinnen in der Datenbank zu suchen.

Nach jeder Eintragung durch eine:n ORF-Redakteur:in wird die Expertin im Sinne der Datenschutzgrundverordnung kontaktiert und um ihre Einverständnis gebeten. Aus Datenschutzgründen ist die Expertinnen-Datenbank ein ORF-internes Tool und dementsprechend nicht öffentlich zugänglich. Die Expertinnen-Datenbank ist ein Service für ORF-Redakteur:innen unter strikter Beachtung der geltenden ORF-Regulative zu Unabhängigkeit, Unvereinbarkeit und Glaubwürdigkeit der Berichterstattung.

Das Ziel der Expertinnen-Datenbank ist, die Sichtbarkeit und Wahrnehmbarkeit von Fachfrauen in den ORF-Medien Fernsehen, Radio und Online zu verbessern bzw. zu erhöhen. Die Expertinnen-Datenbank ist eine Initiative der ORF Gleichstellung und des Public Value Kompetenzzentrums.

Denk|Raum zum Thema "Wer ist eine Expert:in?" mit Claudia

Reiterer, Lou Lorenz-Dittlbacher und Peter Filzmaier

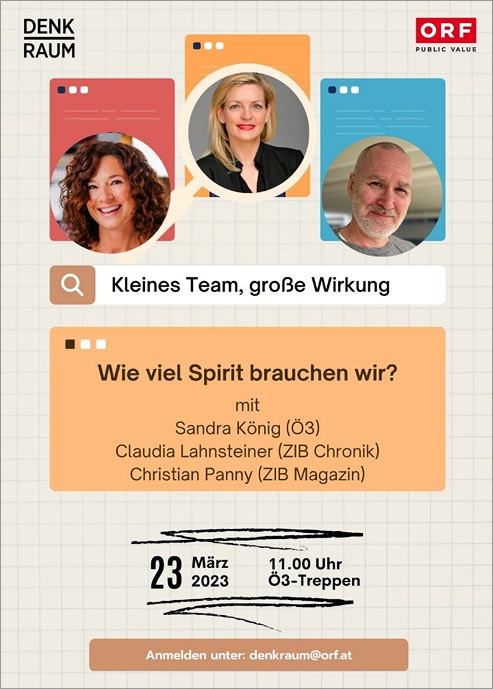

Denk|Raum zum Thema "Kleines Team, große Wirkung. Wie viel Spirit brauchen wir?" mit Sandra König, Claudia Lahnsteiner und Christian Panny

Eine kleine Auswahl an Denk|Räumen, die bereits stattgefunden haben:

Wenn Du dich dafür interessierst und mitmachen willst oder Vorschläge für Themen hast, die wir behandeln sollten, schreib eine E-Mail an denkraum@orf.at.

Philipp Maschl, ORF-News

Lukas Klingan, Generaldirektion

Mariella Gittler, ORF-News

Isabelle Richter, ORF Public Value

Livestream am 23. Mai ab 13.00 Uhr auf zukunft.ORF.at

Ist Medienqualität mehr als eine Behauptung? Wer definiert sie? Wer beurteilt, bewertet

13.00

Harald Fidler, "Der Standard"

Susanne Schnabl, ORF "Report"

Armin Thurnher, "Falter"

14.00

Sabine Funk, ORF-Medienforschung

Susanne Kayser, ZDF Public Value

Thomas Steinmaurer, Universität Salzburg

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger, ORF Public Value

Die DialogForen werden zeitversetzt auf ORF III Kultur und Information ausgestrahlt.

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger, ORF Public Value

In Kooperation mit der Schwedischen Botschaft, dem European Forum Alpbach und dem Alumniverband der Universität Wien.

Die DialogForen werden live gestreamt und zeitversetzt auf ORF III Kultur und Information ausgestrahlt.

Der ORF ist der größte Auftraggeber der österreichischen Film- und Fernsehwirtschaft. Jedes Jahr investiert er rund 100 Millionen in den Film- und Produktionsstandort Österreich.

Der ORF ist der größte Auftraggeber der österreichischen Film- und Fernsehwirtschaft. Jedes Jahr investiert er rund 100 Millionen in den Film- und Produktionsstandort Österreich.

Grund genug zu fragen: Was macht den "österreichischen Film" eigentlich aus? Was unterscheidet öffentlich-rechtliche Filmproduktion von kommerzieller? Wie geht es in Zukunft weiter?

Im ORF-DialogForum diskutieren:

Sebastian Höglinger, Geschäftsführer der "Diagonale"

John Lueftner, Präsident der "Association of Austrian Filmproducers"

Katharina Schenk, ORF-Fernsehfilm

Kurt Brazda, Filmregisseur

Arash T. Riahi, Präsident der "Akademie des Österreichischen Films"

Clara Stern, Filmregisseurin

sowie

Michael Petzl, Landesschulsprecher Wien

Katharina Settele, Schauspielerin

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger

am 15.3.2023 im ORF- RadioKulturhaus

Livestream ab 13:00 Uhr auf zukunft.ORF.at.

Hinweis im Sinne des Kinos

1 Kinoabo - 18 Kinos - unbegrenzt Kinofilme sehen

Seit dem 16. März gibt es das "nonstop"-Kinoabo, mit dem es möglich ist, für 22 Euro pro Monat

18 ausgewählte Kinos in ganz Österreich zu besuchen.

Alle weiteren Informationen unter www.nonstopkino.at

Instagram: nonstopkino

Der erfolgreichste Unternehmer.

Der erfolgreichste Unternehmer.

Die schönste Frau.

Das beste Auto.

Die Superlative überbieten sich ebenso wie die Stereotype. Doch was bedeuten sie? Wer bestimmt, was ausgezeichnet wird? Was als vorbildhaft und anstrebenswert angesehen wird? Und nicht zuletzt: Was ist eigentlich (Medien-)Qualität und wem nützt sie?

Was gemeint ist, wenn von "Qualität" die Rede ist, diskutieren im ORF DialogForum

Franz Essl, Wissenschaftler des Jahres 2022

Wanda Moser-Heindl, Gründerin der SozialMarie

Daniela Kraus, Generalsekretärin des Presseclub Concordia

Florian Klenk, Chefredakteur des Falter

Mathias Huter, Obmann des Forum Informationsfreiheit

Jasmin Chalendi, Politologin und Jus-Studentin

Daniel Waidinger, Bundes und Wiener Landesjugendreferent YOUNG younion

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger

am 26.1.2023 im ORF- RadioKulturhaus

Livestream ab 13:00 Uhr auf zukunft.ORF.at.

2022 wurde vom Public Value-Kompetenzzentrum des ORF ein Expert:innengespräch zum Bereich "Unterhaltung" durchgeführt: Expert:innen aus Wissenschaft, Medien, Kunst und Kultur diskutierten in zwei mehrstündigen, strukturierten Gesprächen mit ORF-Vertreter:innen die Qualität der ORF-Unterhaltungsangebote in Radio, Fernsehen und online.

2022 wurde vom Public Value-Kompetenzzentrum des ORF ein Expert:innengespräch zum Bereich "Unterhaltung" durchgeführt: Expert:innen aus Wissenschaft, Medien, Kunst und Kultur diskutierten in zwei mehrstündigen, strukturierten Gesprächen mit ORF-Vertreter:innen die Qualität der ORF-Unterhaltungsangebote in Radio, Fernsehen und online. Am 20.10.2022 organisierte das Public Value Kompetenzzentrum des ORF den zweiten "Zukunftsdialog - next generation", zu dem es junge Menschen aus ganz Österreich einlud, um die Zukunft des ORF zu diskutieren.

Am 20.10.2022 organisierte das Public Value Kompetenzzentrum des ORF den zweiten "Zukunftsdialog - next generation", zu dem es junge Menschen aus ganz Österreich einlud, um die Zukunft des ORF zu diskutieren. Am 11. Oktober 2023 fand das DialogForum "ZUSAMMEN - aber Wohin?" im Radiokulturhaus in Wien statt.

Am 11. Oktober 2023 fand das DialogForum "ZUSAMMEN - aber Wohin?" im Radiokulturhaus in Wien statt.

Krisen, Krieg und Katastrophenstimmen beherrschen die Schlagzeilen.

Bestimmen sie auch das Stimmungsbild und vor allem die Perspektiven der Menschen?

Gibt es positive Zukunftsbilder, jenseits der dystopischen Szenarien und Realitäten.

Diesen und anderen Fragen stellten sich:

Carmen Bayer, Armutskonferenz Salzburg

Franz Neunteufl, Interessensvertretung gemeinnütziger Organisationen

Esra Özmen, Musikerin

Sinus Zagar, Mitwirkender im Klimarat

Eva Sabine Kuntz, Deutschlandradio

Gini Lampl, TikTokerin

Robert Misik, Autor

Wolfgang Wagner, ORF-"Report"

Die gesamte Sendung - moderiert von Klaus Unterberger - finden Sie hier.

Für den ORF und alle öffentlich-rechtlichen Medien in Europa bringt 2023 neue Herausforderungen, Aufgaben, aber auch Chancen: Wie kann es gelingen mit den "Social-Media"-Angeboten von Facebook, TikTok, YouTube und Instagram Schritt zu halten? Was wird neu und anders? Wie kann der öffentlich-rechtliche Auftrag im digitalen Zeitalter erfüllt werden? Und nicht zuletzt: Wie können eigene Defizite und Strukturmängel überwunden werden?

Für den ORF und alle öffentlich-rechtlichen Medien in Europa bringt 2023 neue Herausforderungen, Aufgaben, aber auch Chancen: Wie kann es gelingen mit den "Social-Media"-Angeboten von Facebook, TikTok, YouTube und Instagram Schritt zu halten? Was wird neu und anders? Wie kann der öffentlich-rechtliche Auftrag im digitalen Zeitalter erfüllt werden? Und nicht zuletzt: Wie können eigene Defizite und Strukturmängel überwunden werden?

Karen Donders, Director of Public Value (VRT)

Gerald Heidegger, Online Editor (ORF)

Smilla Buschbom, Jugendrat Wien

Michael Farthofer, Studierender an der Universität Wien

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger

Krisen, Krieg und Katastrophenstimmen beherrschen die Schlagzeilen. Bestimmen sie auch das Stimmungsbild und vor allem die Perspektiven der Menschen? Wohin bewegt sich unsere Gesellschaft? In Verunsicherung und Angst? Ist sozialer Zusammenhalt noch möglich, trotz Polarisierung und Segmentierung? Gibt es positive Zukunftsbilder, jenseits der dystopischen Szenarien und Realitäten? Beteiligen sich Medien an der Empörungsbewirtschaftung oder an der Suche nach dem "neuen WIR"?

Krisen, Krieg und Katastrophenstimmen beherrschen die Schlagzeilen. Bestimmen sie auch das Stimmungsbild und vor allem die Perspektiven der Menschen? Wohin bewegt sich unsere Gesellschaft? In Verunsicherung und Angst? Ist sozialer Zusammenhalt noch möglich, trotz Polarisierung und Segmentierung? Gibt es positive Zukunftsbilder, jenseits der dystopischen Szenarien und Realitäten? Beteiligen sich Medien an der Empörungsbewirtschaftung oder an der Suche nach dem "neuen WIR"?Carmen Bayer, Armutskonferenz Salzburg

Franz Neunteufl, Interessensvertretung gemeinnütziger Organisationen

Esra Özmen, Musikerin

Sinus Zagar, Mitwirkender im Klimarat

14.00 Uhr

Eva Sabine Kuntz, Deutschlandradio

Gini Lampl, TikTokerin

Robert Misik, Autor

Wolfgang Wagner, ORF-"Report"

Moderation: Klaus Unterberger, ORF Public Value

Dienstag, 11. Oktober 2022

Die DialogForen werden auf zukunft.ORF.at live gestreamt. Die Sendung ist außerdem am Mittwoch, 02.11.22 von 00:15-01:15 Uhr sowie Samstag, 05.11. von 08:30-09:30 Uhr auf ORF III zu sehen und steht danach für 7 Tage in der Mediathek zum Abruf bereit.

RIPE, the most important academic conference on public service media, met in Vienna in 2022 and provided a forum to address diverse aspects of the media quality discourse from the perspective of diverse European research institutions. This year's keynote address "The War against the BBC - What's at Stake and Why it Matters" was given by Patrick Barwise. The LIVE STREAM of the first day of the conference at ORF - including the keynote speech - can also be found here.

RIPE, the most important academic conference on public service media, met in Vienna in 2022 and provided a forum to address diverse aspects of the media quality discourse from the perspective of diverse European research institutions. This year's keynote address "The War against the BBC - What's at Stake and Why it Matters" was given by Patrick Barwise. The LIVE STREAM of the first day of the conference at ORF - including the keynote speech - can also be found here.

The War against the BBC -

What's at Stake and Why It Matters

Keynote @RIPE2022 by Patrick Barwise

When Peter York and I began researching our book five years ago, some people thought the title - the war against the BBC - overstated. No one says that now. The 'war' we describe is a civil war within Britain. Autocrats and demagogues around the world also attack the BBC. But the book is about people attacking it in the UK. This is part of a worldwide drift towards reduced democratic freedom and accountability, weakened independent media and, as I'll show, less well-informed publics.

The book's subtitle is 'How an unprecedented combination of hostile forces is destroying Britain's greatest cultural institution… and why you should care'. Of course, the hostile forces include technology and consumption trends, online competitors and rising costs.

But they also include the deliberate influence of commercial and political vested interests, reinforced by free-market ideology.

Some commercial media leaders see the BBC as unhelpful competition, reducing their revenue and profit. The fact that this perception is largely unfounded doesn't help. Rupert Murdoch, in particular, has long claimed it crowds out commercial media, actually reducing consumer choice.

When Sky was part of his empire, he claimed that BBC TV provided unfair competition to it and BBC Online - by offering high-quality, open access, highly trusted, advertising-free online news and other content - materially reduced newspapers' online income. Having now sold his interest in Sky and invested in UK commercial radio, his attacks have switched to BBC Radio.

In reality, studies have consistently found no evidence that the BBC crowds out commercial media. There is even some evidence of the opposite: a 14-country study in 2013 found that, with the marked exception of the USA, countries with strong PSBs tended to have stronger commercial broadcasters, measured by per capita revenue. And US newspapers, with no BBC, find it just as hard to generate online advertising revenue to replace lost print revenue. In 2019, a government-commissioned review on financially sustainable journalism specifically rejected claims that BBC Online threatened UK newspapers, arguing instead that, 'curtailing the BBC's news offering would be counter-productive [as] the BBC offers the very thing this review aims to encourage: a source of reliable and high-quality news, with a focus on objectivity and impartiality, and independent from government'.

Because PSBs now deliver their mission online as well as through broadcast channels, many people - including this conference - prefer the term public service media or PSM. That's fine - as Juliet says of Romeo, 'what's in a name?' - unless it makes you underplay the continuing importance of broadcasting. All PSM are still mainly broadcasters in the sense that most of their money still goes into creating TV and radio content. They now distribute that content using both broadcast and online channels - but that, to me, is a secondary issue. We can all pretty much agree that a PSB is a national broadcaster whose licence requires it, as far as possible, to be universally available, deliver specific social benefits - not just entertainment - and be editorially independent.

The definition of PSM is, to me, less clear. For instance, does it include The Guardian, which certainly has a public service mission and is open source, non-profit and partly funded by voluntary donations?

Broadcasting is still enormously important.

The average Brit still consumes the BBC's services for two-and-a-half hours a day! 90 per cent of that is of TV and radio content - mostly consumed on broadcast channels. Those attempting a political or military coup still try to take over the national broadcaster to control the public's most important information source. And Russian state TV has been central to the Kremlin's - still largely successful - effort to build and sustain public support for the Ukraine war.

Even in stable democracies, politicians inevitably try to influence PSBs' political coverage - and the more widely consumed and highly trusted the PSB, the greater their motivation to do so. In Britain, it's a lot. In the US, not at all, except in its early days under Richard Nixon.

Nor are commercial and political vested interests always distinct. According to The Economist, when Silvio Berlusconi was the Italian prime minister, he controlled - among other media - 90 per cent of national TV broadcasting, either directly through his privately owned channels or indirectly by appointing supporters to manage RAI.

In Britain, the links between commercial and political vested interests aren't so extreme. But Rupert Murdoch, in particular, has used his control of the biggest newspaper group to build mutually beneficial relationships with most prime ministers since 1979, including Labour's Tony Blair.

These relationships are invariably bad for the BBC: Blair is the only prime minister who has ever forced the resignation of the BBC's chairman and director general.

It would be naive not to see this as a sort-of conspiracy.

Not a mad, overarching conspiracy like QAnon, more one where people with overlapping interests talk offline and co-ordinate their actions.

This is the bread and butter of local, national, international and organisational politics.

Whatever the specifics, all publicly-funded PSBs are now squeezed between reduced funding and ever-rising costs and competition.

In BBC's the case, the funding cuts since 2010 are much deeper than most people realise.

After the Conservatives' 2015 election victory, finance minister George Osborne had six secret meetings in eight weeks with Murdoch executives, including two with Murdoch himself. He then imposed the deepest ever cut in BBC funding - on top of one he'd already imposed in 2010.

By 2019, the real (inflation-adjusted) public funding of the BBC's UK services was 30 per cent down on 2010.

The BBC clawed some of that back through its much criticised decision to limit free TV licences for the over-75s to those in poorer households - and then persuading over 90 per cent of those no longer eligible to pay up.

But in January, the government announced another two-year licence fee freeze. With 9 per cent annual inflation, that will increase the cumulative cut in real funding since 2010 to almost 40 per cent by March 2024, with possibly worse to come.

The BBC has so far managed to protect its services through efficiency gains, commercial income growth and trimmed programme budgets.

But, as the cuts continue, it will increasingly have to replace expensive programmes like high-end dramas and natural history shows with cheaper ones and more repeats.

The risk is that this creates a vicious circle, with more people refusing to pay the licence fee, further reducing programme budgets, and so on, leading to a crisis sometime in the next four-to-five years.

PSBs in smaller countries have it even worse because their income depends on the population size, while production costs are fixed.

DR, the Danish PSB, once told me there are more boy scouts in the world than Danish speakers…

On top of these financial pressures and technology challenges, PSBs also face endless attacks on the accuracy and impartiality of their news coverage.

In the BBC's case, efforts to persuade the public not to trust it have, so far, been largely unsuccessful.

If UK adults are asked, 'Which ONE news source would you turn to for news you trust the most?', the BBC, on 51 per cent, completely dominates the responses, followed by ITV on 9 per cent, Sky 6 per cent, The Guardian 4 per cent, and Channel 4 4 per cent.

None of the right-wing anti-BBC newspapers gets more than 1 per cent - the same as Al Jazeera, Twitter and Facebook.

Government attacks on the BBC's impartiality are always framed as attempts to rectify a supposed left-wing bias. But is the BBC's news coverage systematically biased to the left?

In The War Against the BBC, we look at this in some detail.

None of the BBC's respectable critics - newspapers, politicians, think tanks - has ever seriously claimed that its news coverage is inaccurate.

Instead, the claim is that it is biased in its choice of topics (and how these are framed) and interviewees (and how they are interviewed).

In both football refereeing and news reporting, bias is very much in the eye of the beholder. So who's right about 'BBC bias'?

The best evidence is from Cardiff University analysis of the BBC's UK news coverage in 2007 and 2012.

This suggests that BBC News was marginally biased in favour of the government of the day in both years - but this bias was somewhat more when the Conservatives were in power in 2012 than under Labour in 2007 - the exact opposite of the repeated claim of left-wing bias.

Nor do perceptions among the general public support the claim that the BBC's news coverage is biased to the left.

Those who are older, socially conservative and right-leaning do tend to agree with this claim, but they are in a minority. An almost equal number - typically younger, socially liberal and left-leaning - see the BBC as biased to the right (and part of the 'Establishment'); while a large number in between see it as broadly impartial.

So, if the best evidence is that the BBC's news coverage doesn't systematically lean to the left, and most of the public don't think it leans to the left, why are most of the attacks on it from the right?

When we started researching the book, we expected to find some imbalance, with slightly more attacks from the right than from the left.

What we found was much more extreme: the organised attacks on the BBC - by people, as part of their day jobs at newspapers, political parties and think tanks - are overwhelmingly from the right.

We think there are five possible reasons for this imbalance:

First, ideology: free-marketeers will always see the BBC as an unnecessary or disproportionate 'intervention'. They think its only valid role is to address 'market failure', showing public service content that the market can't provide.

Secondly, commercial vested interests are mostly right-leaning.

Thirdly, resources: right-wing UK think tanks and political parties are better - and more opaquely - funded than those on the left.

Fourth, outlets: most UK newspapers lean to the right, especially if weighted by readership. (And yes, they still matter a lot).

Finally, what we've called the 'silent majority illusion': at least anecdotally, many on the right seem to be more likely (albeit mistakenly) to think most other people agree with them.

In summary: the BBC and other PSBs face an unprecedented combination of technology, consumption and market trends and deliberate undermining by hostile forces, overwhelmingly from the right.

But the biggest challenges are financial, especially for those, like the BBC, whose core funding is set by governments. They are caught between deep funding cuts, higher content and distribution costs, and ever-increasing competition.

Why should we care?

With burgeoning choice from pay TV and, now, the streamers, would it matter if, after 100 years - the BBC's centenary is next month - we were to lose PSB and leave broadcasting entirely to the market?

The answer is emphatically yes.

One reason is to do with universal access and shared experience: it's complicated, but the non-PSBs are typically available only to those willing and able to pay for them.

A second reason is that a well-run PSB is extremely good value for money - although achieving that is harder in a country with a small population.

Even in Britain, with 26 million households, people take the BBC for granted and argue that they shouldn't have to pay for it if they don't use it.

But in 2015 - the only time it's been measured - 99 per cent of households used its TV, radio or online services in a week.

The idea that a material number are forced to pay £159 and get no benefit over a whole year is nonsense.

Also in 2015, the BBC ran a study in which households that said the licence fee was not good value for money were paid to spend nine days with no BBC.

After nine days, 68% changed their minds, deciding it was good value for money, after all!

And when the study was repeated late last year, this proportion actually increased to 70%. The increase wasn't statistically significant, but nevertheless!

Finally, I argued earlier that if the challenges facing PSBs lead to a weakening of PSBs around the world, that will reinforce the drift towards reduced democratic freedom and accountability, weakened independent media, and less well-informed publics.

We now have direct evidence on the last point, about PSB's role in ensuring a well-informed public - the importance of which hardly needs stressing with a war in Europe and all the other challenges we're now facing.

A recent study by Zurich and Antwerp Universities compared the public's resilience to online disinformation in 18 countries. The strength of their PSBs was one of the key factors associated with greater resilience.

The most resilient countries were in northern and western Europe, led by the Nordics - closely followed by Britain, partly thanks to its strong PSB system, with the BBC at its heart.

Southern European countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece had more credulous populations.

And the US was in a category of its own, its population 'particularly susceptible' to disinformation.

Of course, there are many reasons for US vulnerability to online disinformation. But its weak PSB is one factor, as is the 1987 abolition of the Fairness Doctrine for broadcast news, opening the door to Fox News and shock jock radio - years before the social media that are now spreading the disinformation and reinforcing the divisions in US society.

Strong, properly funded public service broadcasting isn't just 'nice to have'. It's a key part of a healthy democracy. And, right now, it's hard to overstate the importance of the 'war' against it.

So, go out and make the PSBs' case!

Show their continuing usage and the value for money they give their viewers, listeners and online users.

Show their role in the national culture and in creating shared events that bring people together, when so much is driving them apart.

Above all, show the importance of impartial, trusted news that reaches across the whole of society, countering the disinformation and echo chambers that are undermining liberal democracy.

Because, more than anything else, that's what's really at stake.

Thank you.

What's at Stake and Why It Matters

When Peter York and I began researching our book five years ago, some people thought the title - the war against the BBC - overstated. No one says that now.

The 'war' we describe is a civil war within Britain.

Autocrats and demagogues around the world also attack the BBC. But the book is about people attacking it in the UK.

This is part of a worldwide drift towards reduced democratic freedom and accountability, weakened independent media and, as I'll show, less well-informed publics.

The book's subtitle is 'How an unprecedented combination of hostile forces is destroying Britain's greatest cultural institution… and why you should care'.

Of course, the hostile forces include technology and consumption trends, online competitors and rising costs.

But they also include the deliberate influence of commercial and political vested interests, reinforced by free-market ideology.

Some commercial media leaders see the BBC as unhelpful competition, reducing their revenue and profit. The fact that this perception is largely unfounded doesn't help.

Rupert Murdoch, in particular, has long claimed it crowds out commercial media, actually reducing consumer choice.

When Sky was part of his empire, he claimed that BBC TV provided unfair competition to it and BBC Online - by offering high-quality, open access, highly trusted, advertising-free online news and other content - materially reduced newspapers' online income.

Having now sold his interest in Sky and invested in UK commercial radio, his attacks have switched to BBC Radio.

In reality, studies have consistently found no evidence that the BBC crowds out commercial media.

There is even some evidence of the opposite: a 14-country study in 2013 found that, with the marked exception of the USA, countries with strong PSBs tended to have stronger commercial broadcasters, measured by per capita revenue.

And US newspapers, with no BBC, find it just as hard to generate online advertising revenue to replace lost print revenue.

In 2019, a government-commissioned review on financially sustainable journalism specifically rejected claims that BBC Online threatened UK newspapers, arguing instead that, 'curtailing the BBC's news offering would be counter-productive [as] the BBC offers the very thing this review aims to encourage: a source of reliable and high-quality news, with a focus on objectivity and impartiality, and independent from government'.

Because PSBs now deliver their mission online as well as through broadcast channels, many people - including this conference - prefer the term public service media or PSM.

That's fine - as Juliet says of Romeo, 'what's in a name?' - unless it makes you underplay the continuing importance of broadcasting.

All PSM are still mainly broadcasters in the sense that most of their money still goes into creating TV and radio content.

They now distribute that content using both broadcast and online channels - but that, to me, is a secondary issue.

We can all pretty much agree that a PSB is a national broadcaster whose licence requires it, as far as possible, to be universally available, deliver specific social benefits - not just entertainment - and be editorially independent.

The definition of PSM is, to me, less clear. For instance, does it include The Guardian, which certainly has a public service mission and is open source, non-profit and partly funded by voluntary donations?

Broadcasting is still enormously important.

The average Brit still consumes the BBC's services for two-and-a-half hours a day!

90 per cent of that is of TV and radio content - mostly consumed on broadcast channels.

Those attempting a political or military coup still try to take over the national broadcaster to control the public's most important information source.

And Russian state TV has been central to the Kremlin's - still largely successful - effort to build and sustain public support for the Ukraine war.

Even in stable democracies, politicians inevitably try to influence PSBs' political coverage - and the more widely consumed and highly trusted the PSB, the greater their motivation to do so. In Britain, it's a lot. In the US, not at all, except in its early days under Richard Nixon.

Nor are commercial and political vested interests always distinct. According to The Economist, when Silvio Berlusconi was the Italian prime minister, he controlled - among other media - 90 per cent of national TV broadcasting, either directly through his privately owned channels or indirectly by appointing supporters to manage RAI.

In Britain, the links between commercial and political vested interests aren't so extreme. But Rupert Murdoch, in particular, has used his control of the biggest newspaper group to build mutually beneficial relationships with most prime ministers since 1979, including Labour's Tony Blair.

These relationships are invariably bad for the BBC: Blair is the only prime minister who has ever forced the resignation of the BBC's chairman and director general.

It would be naive not to see this as a sort-of conspiracy.

Not a mad, overarching conspiracy like QAnon, more one where people with overlapping interests talk offline and co-ordinate their actions.

This is the bread and butter of local, national, international and organisational politics.

Whatever the specifics, all publicly-funded PSBs are now squeezed between reduced funding and ever-rising costs and competition.

In BBC's the case, the funding cuts since 2010 are much deeper than most people realise.

After the Conservatives' 2015 election victory, finance minister George Osborne had six secret meetings in eight weeks with Murdoch executives, including two with Murdoch himself. He then imposed the deepest ever cut in BBC funding - on top of one he'd already imposed in 2010.

By 2019, the real (inflation-adjusted) public funding of the BBC's UK services was 30 per cent down on 2010.

The BBC clawed some of that back through its much criticised decision to limit free TV licences for the over-75s to those in poorer households - and then persuading over 90 per cent of those no longer eligible to pay up.

But in January, the government announced another two-year licence fee freeze. With 9 per cent annual inflation, that will increase the cumulative cut in real funding since 2010 to almost 40 per cent by March 2024, with possibly worse to come.

The BBC has so far managed to protect its services through efficiency gains, commercial income growth and trimmed programme budgets.

But, as the cuts continue, it will increasingly have to replace expensive programmes like high-end dramas and natural history shows with cheaper ones and more repeats.

The risk is that this creates a vicious circle, with more people refusing to pay the licence fee, further reducing programme budgets, and so on, leading to a crisis sometime in the next four-to-five years.

PSBs in smaller countries have it even worse because their income depends on the population size, while production costs are fixed.

DR, the Danish PSB, once told me there are more boy scouts in the world than Danish speakers…

On top of these financial pressures and technology challenges, PSBs also face endless attacks on the accuracy and impartiality of their news coverage.

In the BBC's case, efforts to persuade the public not to trust it have, so far, been largely unsuccessful.

If UK adults are asked, 'Which ONE news source would you turn to for news you trust the most?', the BBC, on 51 per cent, completely dominates the responses, followed by ITV on 9 per cent, Sky 6 per cent, The Guardian 4 per cent, and Channel 4 4 per cent.

None of the right-wing anti-BBC newspapers gets more than 1 per cent - the same as Al Jazeera, Twitter and Facebook.

Government attacks on the BBC's impartiality are always framed as attempts to rectify a supposed left-wing bias. But is the BBC's news coverage systematically biased to the left?

In The War Against the BBC, we look at this in some detail.

None of the BBC's respectable critics - newspapers, politicians, think tanks - has ever seriously claimed that its news coverage is inaccurate.

Instead, the claim is that it is biased in its choice of topics (and how these are framed) and interviewees (and how they are interviewed).

In both football refereeing and news reporting, bias is very much in the eye of the beholder. So who's right about 'BBC bias'?

The best evidence is from Cardiff University analysis of the BBC's UK news coverage in 2007 and 2012.

This suggests that BBC News was marginally biased in favour of the government of the day in both years - but this bias was somewhat more when the Conservatives were in power in 2012 than under Labour in 2007 - the exact opposite of the repeated claim of left-wing bias.

Nor do perceptions among the general public support the claim that the BBC's news coverage is biased to the left.

Those who are older, socially conservative and right-leaning do tend to agree with this claim, but they are in a minority. An almost equal number - typically younger, socially liberal and left-leaning - see the BBC as biased to the right (and part of the 'Establishment'); while a large number in between see it as broadly impartial.

So, if the best evidence is that the BBC's news coverage doesn't systematically lean to the left, and most of the public don't think it leans to the left, why are most of the attacks on it from the right?

When we started researching the book, we expected to find some imbalance, with slightly more attacks from the right than from the left.

What we found was much more extreme: the organised attacks on the BBC - by people, as part of their day jobs at newspapers, political parties and think tanks - are overwhelmingly from the right.

We think there are five possible reasons for this imbalance:

First, ideology: free-marketeers will always see the BBC as an unnecessary or disproportionate 'intervention'. They think its only valid role is to address 'market failure', showing public service content that the market can't provide.

Secondly, commercial vested interests are mostly right-leaning.

Thirdly, resources: right-wing UK think tanks and political parties are better - and more opaquely - funded than those on the left.

Fourth, outlets: most UK newspapers lean to the right, especially if weighted by readership. (And yes, they still matter a lot).

Finally, what we've called the 'silent majority illusion': at least anecdotally, many on the right seem to be more likely (albeit mistakenly) to think most other people agree with them.

In summary: the BBC and other PSBs face an unprecedented combination of technology, consumption and market trends and deliberate undermining by hostile forces, overwhelmingly from the right.

But the biggest challenges are financial, especially for those, like the BBC, whose core funding is set by governments. They are caught between deep funding cuts, higher content and distribution costs, and ever-increasing competition.

Why should we care?

With burgeoning choice from pay TV and, now, the streamers, would it matter if, after 100 years - the BBC's centenary is next month - we were to lose PSB and leave broadcasting entirely to the market?

The answer is emphatically yes.

One reason is to do with universal access and shared experience: it's complicated, but the non-PSBs are typically available only to those willing and able to pay for them.

A second reason is that a well-run PSB is extremely good value for money - although achieving that is harder in a country with a small population.

Even in Britain, with 26 million households, people take the BBC for granted and argue that they shouldn't have to pay for it if they don't use it.

But in 2015 - the only time it's been measured - 99 per cent of households used its TV, radio or online services in a week.

The idea that a material number are forced to pay £159 and get no benefit over a whole year is nonsense.

Also in 2015, the BBC ran a study in which households that said the licence fee was not good value for money were paid to spend nine days with no BBC.

After nine days, 68% changed their minds, deciding it was good value for money, after all!

And when the study was repeated late last year, this proportion actually increased to 70%. The increase wasn't statistically significant, but nevertheless!

Finally, I argued earlier that if the challenges facing PSBs lead to a weakening of PSBs around the world, that will reinforce the drift towards reduced democratic freedom and accountability, weakened independent media, and less well-informed publics.

We now have direct evidence on the last point, about PSB's role in ensuring a well-informed public - the importance of which hardly needs stressing with a war in Europe and all the other challenges we're now facing.

A recent study by Zurich and Antwerp Universities compared the public's resilience to online disinformation in 18 countries. The strength of their PSBs was one of the key factors associated with greater resilience.

The most resilient countries were in northern and western Europe, led by the Nordics - closely followed by Britain, partly thanks to its strong PSB system, with the BBC at its heart.

Southern European countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece had more credulous populations.

And the US was in a category of its own, its population 'particularly susceptible' to disinformation.

Of course, there are many reasons for US vulnerability to online disinformation. But its weak PSB is one factor, as is the 1987 abolition of the Fairness Doctrine for broadcast news, opening the door to Fox News and shock jock radio - years before the social media that are now spreading the disinformation and reinforcing the divisions in US society.

Strong, properly funded public service broadcasting isn't just 'nice to have'. It's a key part of a healthy democracy. And, right now, it's hard to overstate the importance of the 'war' against it.

So, go out and make the PSBs' case!

Show their continuing usage and the value for money they give their viewers, listeners and online users.

Show their role in the national culture and in creating shared events that bring people together, when so much is driving them apart.

Above all, show the importance of impartial, trusted news that reaches across the whole of society, countering the disinformation and echo chambers that are undermining liberal democracy.

Because, more than anything else, that's what's really at stake.

Thank you.

https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/press-releases/article/bosnia-and-herzegovina-bhrt-public-service-media-workers-protest-against-organisations-systematic.html

https://www.ebu.ch/news/2022/03/bosnia-herzegovina-public-service-broadcaster-threatened-with-closure